|

| *****SWAAG_ID***** | 1012 | | Date Entered | 27/05/2020 | | Updated on | 14/06/2021 | | Recorded by | Will Swales | | Category | Archaeological Find | | Record Type | Archaeology | | SWAAG Site Name | | | Site Type | | | Site Name | | | Site Description | | | Site Access | Private | | Record Date | 27/05/2020 | | Location | Fremington | | Civil Parish | Reeth | | Brit. National Grid | SE 04 99 | | Altitude | 180 | | Geology | | | Record Name | Fremington Bronze Age axe heads | | Record Description | Among items recently added to the British Museum’s online catalogue are photographs of two Bronze Age, copper-alloy, axe-heads, described as found with others at Reeth in Swaledale, possibly part of a hoard.

Confusingly, nineteenth-century labels on the objects, which are visible on the photographs, denote they were found at Fremington Edge, a high ridge on the opposite side of the dale from Reeth. A brief provenance explains that they were in the collection of Rev William Greenwell and were donated to the museum in 1909 by John Pierpont Morgan.

Greenwell almost certainly wrote the labels on the objects. His separate notes about who owned the axe-heads before him are given online but they leave many questions unanswered. This article draws on multiple sources to try to piece together more of the story of where and when the axe-heads were found and discovers interesting ideas about how they might have been used by Bronze Age men and women.

Reported find of four axe-heads in about 1785

The earliest surviving report of the find appeared in Thomas Dunham Whitaker’s An History of Richmondshire, published in 1823. He wrote (p. 315) – ‘About half a mile eastward [of Maiden Castle] are several deep entrenchments extending in the same direction; one of which crosses the whole vale, pointing on Reeth and Fremington, near which, about the year 1785, four brass celts were dug up’.

Whether four axe-heads count as a hoard can be debated. If there were four, then shortly after Whitaker’s book was published two of them disappeared from public knowledge. ‘Celts’ was the term used at the time to identify ancient cutting tools. The OED definition of ‘celt’ is ‘an implement with a chisel-shaped edge, of bronze or stone (but sometimes of iron), found among the remains of prehistoric man. It appears to have served for a variety of purposes, as a hoe, chisel, or axe, and perhaps as a weapon of war’.

Whitaker’s description of the dyke is peculiar. It does not cross the dale from Reeth to Fremington, as he implies, but from near Grinton to Fremington. At Low Fremington it climbs up the dale-side, about 50 metres in height, ending just above High Fremington. To reach Fremington Edge is another 200-metre climb over a distance of 750 metres. So, there is quite a gulf between Whitaker’s account of the find-spot ‘near the dyke’ and the one indicated on the objects’ labels as Fremington Edge.

Greenwell’s acquisitions - the mid-to-late 1800s

Rev Canon William Greenwell was born in 1820 and hailed from Greenwell Ford, County Durham. He was one of the most prominent archaeologists of his era and a major collector of prehistoric finds. According to Greenwell’s notes, he was given the axe-head that now has the museum catalogue reference WG 1820 by John Bailey Langhorne, who Greenwell recorded as a nephew of the owner of the land on which it was found.

From other sources we learn that John Bailey Langhorne was a wealthy solicitor who lived from 1816 to 1877. He was born in Berwick-upon Tweed, the son of John Langhorne, a banker. John Bailey Langhorne became the proprietor of the Newcastle Chronicle and by 1845 he was living at Richmond in Swaledale and serving as the deputy registrar of the Archdeaconry of Richmond. He was related to Canon Greenwell through one of his grandmothers, who was a Greenwell (Bill Greenwell, see link below).

The identity of the uncle on whose land the axe-head was found is not known, although there are clues. There was a Rev John Langhorne who was curate of Grinton for more than 40 years from as early as 1766. He served under three vicars who according to the parish-record entries for baptisms, marriages and funerals left almost all the work to Langhorne. He could not have been the uncle of John Bailey Langhorne, but he could have been his great uncle, which was perhaps a fine point of difference easily overlooked in Greenwell’s account.

In 1804 and 05, and probably for many more years, Rev John Langhorne occupied land next to Low Fremington belonging to Arkengarthdale Church (NYCRO ZLB 6.12, church rents). He would have sub-let it to a farmer. The main part of it comprised three large fields bordering the road between Reeth Bridge and the first turn-off for High Fremington. The first two fields are now merged and form the current Reeth Show Ground. The third field, next to the road leading to High Fremington, is only about 120 metres from the dyke, and so potentially fits Whitaker’s description of the find-spot.

According to Greenwell’s notes, the axe-head catalogued by the museum as WG 1821 was bought by a Swaledale farmer at a sale of household goods. The record is partially illegible, but the mention of the sale was followed by the word Rev’d. One might wonder if this was a sale following the death of Rev John Langhorne in 1808. Greenwell reported that the farmer sold the axe-head to a Mr R Little of Carlisle, who sold it to Greenwell. No dates for the transactions are given.

Rev Langhorne had two wealthy sons. The elder, John Langhorne, died in Reeth in 1848, aged 77. The younger, Thomas Langhorne, lived farther up the dale at Kearton, but before the census of 1841 he had moved to the Lake District, and later moved to Derbyshire. Nonetheless he retained ownership of a significant amount of property and land in the Reeth area. Rateable valuations for 1870 recorded him as the owner of six houses in Reeth, the Buck Inn, a slaughterhouse, two stables, and about 45 acres of land in Reeth and Fremington (see link below). He died in 1871 in Derbyshire, aged 93.

The long-standing relationship between the Langhorne family and land at or near Fremington seems to make Rev John Langhorne the favourite for being the first modern owner of both axe-heads.

Report in the year 1881

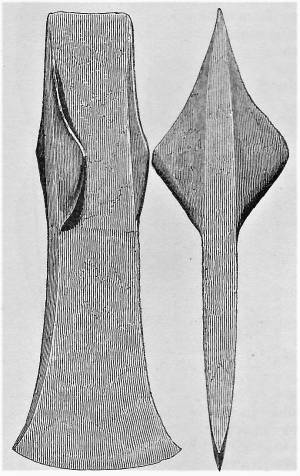

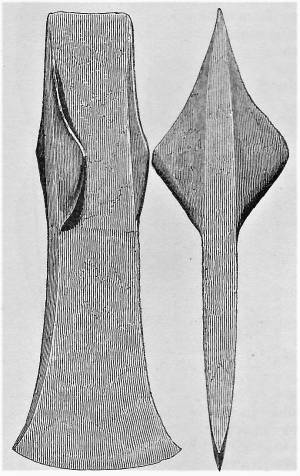

In 1881, one of the axe-heads was featured in a major publication, The Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the third in a series of comprehensive volumes on British prehistoric artefacts by John Evans, a pioneer in the development of professional archaeology in Britain and another major collector of prehistoric objects. Among the 540 wood-cut illustrations in Evans’ book were two views of an axe-head reported as being in the collection of Canon Greenwell and as found ‘with others near Reeth’. By the look of it, it was WG 1820, the one donated by John Bailey Langhorne. It was the better looking of the two Fremington axe-heads, both of which were presumably by this time in Canon Greenwell’s collection.

British Museum acquisition 1908

In 1908 Canon Greenwell sold his entire extensive collection of prehistoric bronze artefacts for £10,000. The buyer was a wealthy America collector, John Pierpont Morgan who the following year donated the lot to the British Museum.

In 1910 the Ordnance Survey researched a revised edition of its 25-inch map of Yorkshire to include, for the first time, references to locations of important archaeological finds. The researchers concluded that the find-spot for the axe-heads was in Low Fremington, just behind Draycott Hall, and in the Grinton-Fremington dyke. The modern OS grid reference is SE 0458 9901. It was marked on the new map, published in 1912, with a new symbol for antiquities and the label ‘Bronze Celts found’. The evidence used to determine the location is unknown, but at this low altitude it could not by any assessment be called Fremington Edge.

In summary

In summary, the so-called ‘Reeth Hoard’ may not have been quite a hoard, and the mention of Reeth is only because it is a bigger and better-known village than its neighbour Fremington, where there are now three possible find-spots. It might have been somewhere very broadly in the vicinity of Fremington Edge; or in Low Fremington in the dyke behind Draycott Hall; or somewhere in the field next to Low Fremington on the east side of Reeth showground. Further research at the British Museum and into the Langhorne family’s land holding around Fremington might prove more enlightening.

| | Dimensions | | | Geographical area | | | Species | | | Scientific Name | | | Common / Notable Species | | | Tree and / or Stem Girth | | | Tree: Position / Form / Status | | | Tree Site ID | 0 | | Associated Site SWAAG ID | | | Additional Notes | Age and uses of the Fremington axe-heads

In 1981, exactly 100 years after the seminal publication by John Evans, the understanding of north British prehistoric axes was advanced by Peter Karl Schmidt and Colin B Burgess who published The Axes of Scotland and Northern England, in the series Prähistorische Bronzefund, Part IX (axes), vol. 7.

The two Fremington axe-heads were categorised as a type called Ulrome, which the authors described as having ‘a gently, evenly S-curved body’. By further explanation, the authors said that when viewed on the broad side, starting from the top, the body bulges slightly, returning to a distinct waist and then turning out to the width of the cutting edge. Schmidt and Burgess noted that the distinctive wings or flanges on the Fremington axe-heads were common to several types, but not indicative of a type on their own.

The authors attributed the date of the Ulrome axe-heads to the so-called Taunton Phase of the Middle Bronze Age (c.1400–1250 BC) and noted that only scattered examples had been found, in north-eastern Britain from Aberdeenshire to Yorkshire. The Reeth finds were the only example of two Ulrome types found together (Schmidt and Burgess pp. 94-99).

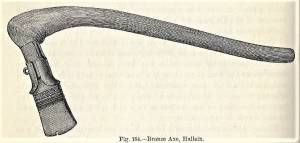

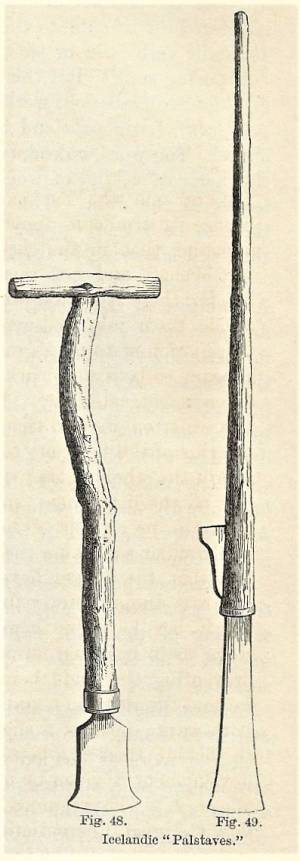

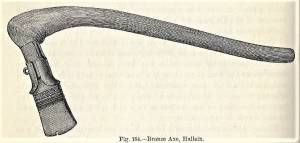

Ulrome axe-heads were not socketed, so to fix a handle, a wooden shaft had to have a splice cut into the end for the wedge-shaped head of the axe to fit into. In 1881, Evans suggested that axe-heads like those found at Fremington could have had their wings hammered around the shaft to create a double socket. The joint would also have been bound with twine.

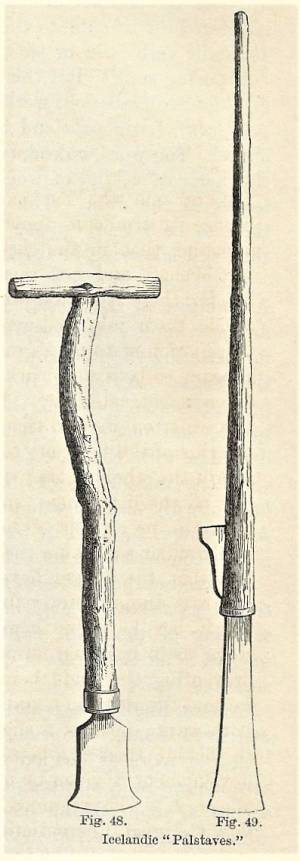

For use as an axe or hatchet, it was necessary for the wooden shaft to have a right-angle turn or crook near the fixing end. But it is also possible that the Fremington axe-heads could have been fitted to the end of a straight shaft. Evans thought that winged axe-heads were particularly suitable for a straight-shafted palstave, which was an Icelandic name for a type of chisel or hoe. Such a tool could have been extremely useful for the job of digging out or ‘stubbing’ thistles in a field. Another such implement was used like a chisel for removing bark from felled timber, in which case it was called a spud.

Links to references above:

British Museum object WG 1820

British Museum object WG 1821

Whitaker’s History of Richmondshire

Greenwell family story

Reeth 1870 valuations

| | Image 1 ID | 7461 Click image to enlarge | | Image 1 Description | British Museum object WG 1820, length 181mm, butt width 31mm, cutting-edge width 69mm. Image copyright © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: British Museum object WG 1820. |  | | Image 2 ID | 7468 Click image to enlarge | | Image 2 Description | British Museum object WG 1820, deepest 50mm, weight 691g. Image copyright © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: British Museum object WG 1820. |  | | Image 3 ID | 7462 Click image to enlarge | | Image 3 Description | British Museum object WG 1821, length 178mm, butt width 27mm, cutting-edge width 69mm. Image copyright © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: British Museum object WG 1821. |  | | Image 4 ID | 7463 Click image to enlarge | | Image 4 Description | British Museum object WG 1821, deepest 39mm, weight 582g. Image copyright © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: British Museum object WG 1821. |  | | Image 5 ID | 7464 Click image to enlarge | | Image 5 Description | One of the Reeth axe heads depicted as a wood-cut illustration in John Evans, The Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland (Longmans, Green & Co., 1881), p. 76, fig. 56. |  | | Image 6 ID | 7465 Click image to enlarge | | Image 6 Description | Section from OS 25-inch map Yorkshire sheet LII.3 Grinton, Reeth, published 1912. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. |  | | Image 7 ID | 7466 Click image to enlarge | | Image 7 Description | Speculative Bronze Age axe, here with a socket fixing depicted as a wood-cut illustration in John Evans, The Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland (Longmans, Green & Co., 1881), p. 152, fig. 184. |  | | Image 8 ID | 7467 Click image to enlarge | | Image 8 Description | Speculative constructions of a palstave or spud depicted as a wood-cut illustration in John Evans, The Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland (Longmans, Green & Co., 1881), p. 71, figs. 48, 49. |  | |